Click to go to Organ Historian Brian Ebie's analysis of Hopkinson's Letter

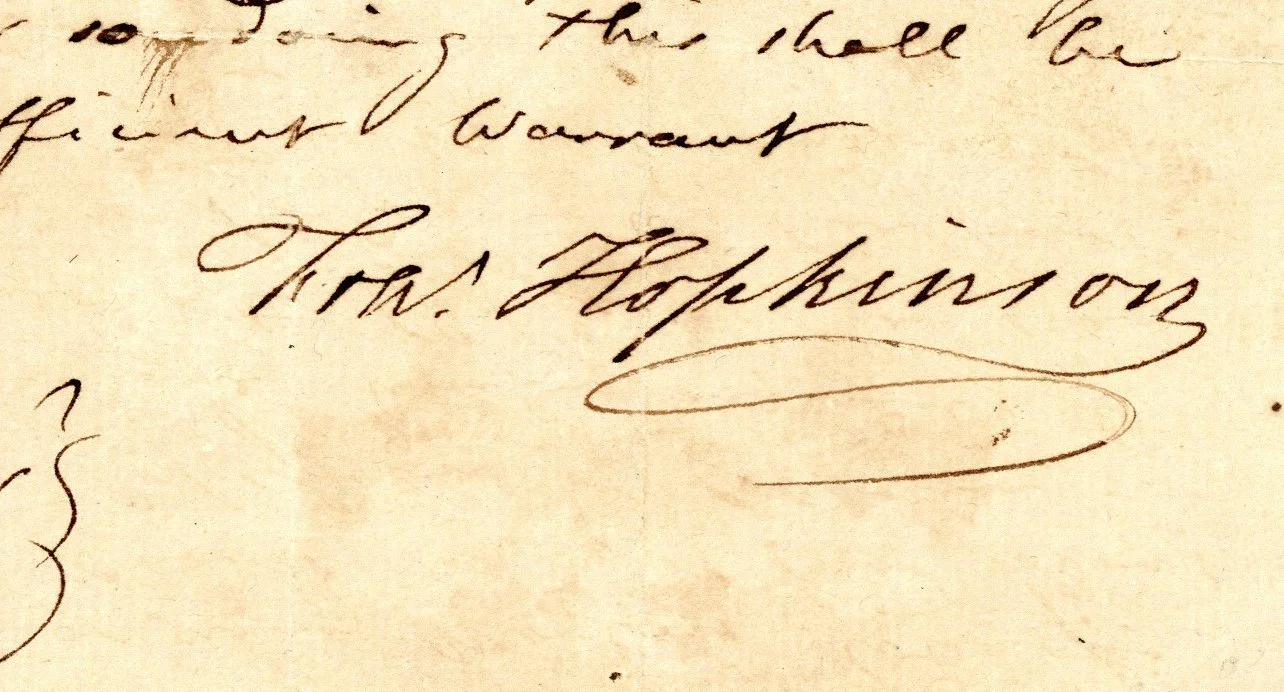

A LETTER TO THE REV. DOCTOR WHITE, RECTOR OF CHRIST CHURCH AND ST. PETER'S ON THE CONDUCT OF A CHURCH ORGAN. Frances Hopkinson

I AM one of those who take great delight in sacred music, and think, with royal David, that heart, voice, and instrument should unite in adoration of the great Supreme.

A soul truly touched with love and gratitude, or under the influence of penitential sorrow, will unavoidably break forth in expressions suited to its feelings. In order that these emanations of the mind may be conducted with uniformity and a becoming propriety, our church hath adopted into her liturgy, the book of psalms, commonly called David's Psalms, which contain a great variety of addresses to the Deity, adapted to almost every state and temperature of a devout heart, and expressed in terms always proper, and often sublime.

TO give wings, as it were to this holy zeal, and heighten the harmony of the soul, organs have been introduced into the churches. The application of instrumental music to the purposes of piety is well known to be of very ancient date. Indeed, originally, it was thought that music ought not to be applied to any other purpose. Modern improvements, however, have discovered, that it may be made expressive of every passion of the mind, and become an incitement to levity as well as sanctity.

UNLESS the real design for which an organ is placed in a church be constantly kept in view, nothing is more likely to happen than an abuse of this noble instrument, so as to render it rather an obstruction to, than an assistant in, the good purpose for which the hearers have assembled.

GIVE me leave, sir, to suggest a few rules for the conduct of an organ in a place of worship, according to my ideas of propriety.

1st. The organist should always keep in mind, that neither the time or place is suitable for exhibiting all his powers of execution; and that the congregation have not assembled to be entertained with his performance. The excellence of an organist consists in his making the instrument subservient and conducive to the purposes of devotion. None but a master can do this. An ordinary performer may play surprising tricks, and shew great dexterity in running through difficult passages, which he hath subdued by dint of previous labour and practice. But he must have judgement and taste who can call forth the powers of the instrument, and apply them with propriety and effect to the seriousness of the occasion.

2nd. The voluntary, previous to reading the lessons, was probably designed to fill up a solemn pause in the service; during which, the clergyman takes a few minutes respite, in a duty too lengthy, perhaps, to be continued without fatigue, unless some intermission be allowed: there, the organ hath its part alone, and the organist an opportunity of shewing his power over the instrument. This, however, should be done with great discretion and dignity, avoiding every thing light and trivial; but rather endeavouring to compose the minds of the audience, and strengthen the tendency of the heart in those devout exercises, in which, it should be presumed, the congregation are now engaged. All sudden jirks, strong contrasts of piano and forte, rapid execution, and expressions of tumult, should be avoided. The voluntary should proceed with great chastity and decorum; the organist keeping in mind, that his hearers are now in the midst of divine service. The full organ should seldom be used on this occasion, nor should the voluntary last more than five minutes of time. Some relaxation, however, of this rule may be allowed, on festivals and grand occasions.

3d. The chants form a pleasing and animating part of the service; but it should be considered, that they are not songs or tunes, but a species of recitative, which is no more than speaking musically. Therefore, as melody or song is out of the question, it is necessary that the harmony should be complete, otherwise chanting, with all the voices in unison, is too light and thin for the solemnity of the occasion. There should at least be half a dozen voices in the organ gallery to fill the harmony with bass and treble parts, and give a dignity to the performance. Melody may be frivolous; harmony, never.

4th. The prelude which the organ plays immediately after the psalm is given out, was intended to advertise the congregation of the psalm tune which is going to be sung; but some famous organist, in order to shew how much he could make of a little, has introduced the custom of running so many divisions upon the simple melody of a psalm tune, that the original purpose of this prelude is now totally defeated, and the tune so disguised by the fantastical flourishes of the dexterous performer, that not an individual in the congregation can possibly guess the tune intended, until the clerk has sung through the first line of the psalm. And it is constantly observable, that the full congregation never join in the psalm before the second or third line, for want of that information which the organ should have given. The tune should be distinctly given out by the instrument, with only a few chaste and expressive decorations, such as none but a master can give.

5th. The interludes between the verses of the psalm were designed to give the singers a little pause, not only to take breath, but also an opportunity for a short retrospect of the words they have sung, in which the organ ought to assist their reflections. For this purpose the organist should be previously informed by the clerk of the verses to be sung, that he may modulate his interludes according to the subject.

TO place this in a strong point of view, no stronger, however, than what I have too frequently observed to happen; suppose the congregation to have sung the first verse of the 33d psalm.

"Let all the just to God with joy

Their chearful voices raise;

For well the righteous it becomes

To sing glad songs of praise."

How dissonant would it be for the organist to play a pathetic interlude in a flat third, with the slender and distant tones of the echo organ, or the deep and smothered sounds of a single diapason stop?

Or suppose again, that the words sung have been the 6th verse of the vith psalm.

"Quite tired with pain, with groaning faint,

No hope of ease I see,

The night, that quiets common griefs

Is spent in tears by me"—

How monstrously absurd would it be to hear these words of distress succeeded by an interlude selected from the fag end of some thundering figure on a full organ, and spun out to a most unreasonable length? Or, what is still worse, by some trivial melody with a rhythm so strongly marked, as to set all the congregation to beating time with their feet or heads? Even those who may be impressed with the feelings such words should occasion, or in the least disposed for melancholy, must be shocked at so gross in impropriety.

THE interludes should not be continued above 16 bars in triple, or ten or twelve bars in common time, and should always be adapted to the verse sung: and herein the organist hath a fine opportunity of shewing his sensibility, and displaying his taste and skill.

6th. The voluntary after service was never intended to eradicate every serious idea which the sermon may have inculcated. It should rather be expressive of that chearful satisfaction which a good heart feels under the sense of a duty performed. It should bear, if possible, some analogy with the discourse delivered from the pulpit; at least, it should not be totally dissonant from it. If the preacher has had for his subject, penitence for sin, the frailty and uncertainty of human life, or the evils incident to mortality, the voluntary may be somewhat more chearful than the tenor of such a sermon might in strictness suggest; but by no means so full and free as a discourse on praise, thanksgiving, and joy, would authorize.

In general, the organ should ever preserve its dignity, and upon no account issue light and pointed movements which may draw the attention of the congregation and induce them to carry home, not the serious sentiments which the service should impress, but some very petty air with which the organist hath been so good as to entertain them. It is as offensive to hear lilts and jiggs from a church organ, as it would be to see a venerable matron frisking through the public street with all the fantastic airs of a columbine.

Click to go to Organ Historian Brian Ebie's complete analysis of Frances Hopkinson's letter.